September 2015. The media frenzy about refugees reaches its peak thanks to the pictures from Budapest and the Hungary-Serbia border. However, these were only two points on their long journey through Europe. This was also one of the routes the refugees followed to reach the continent.

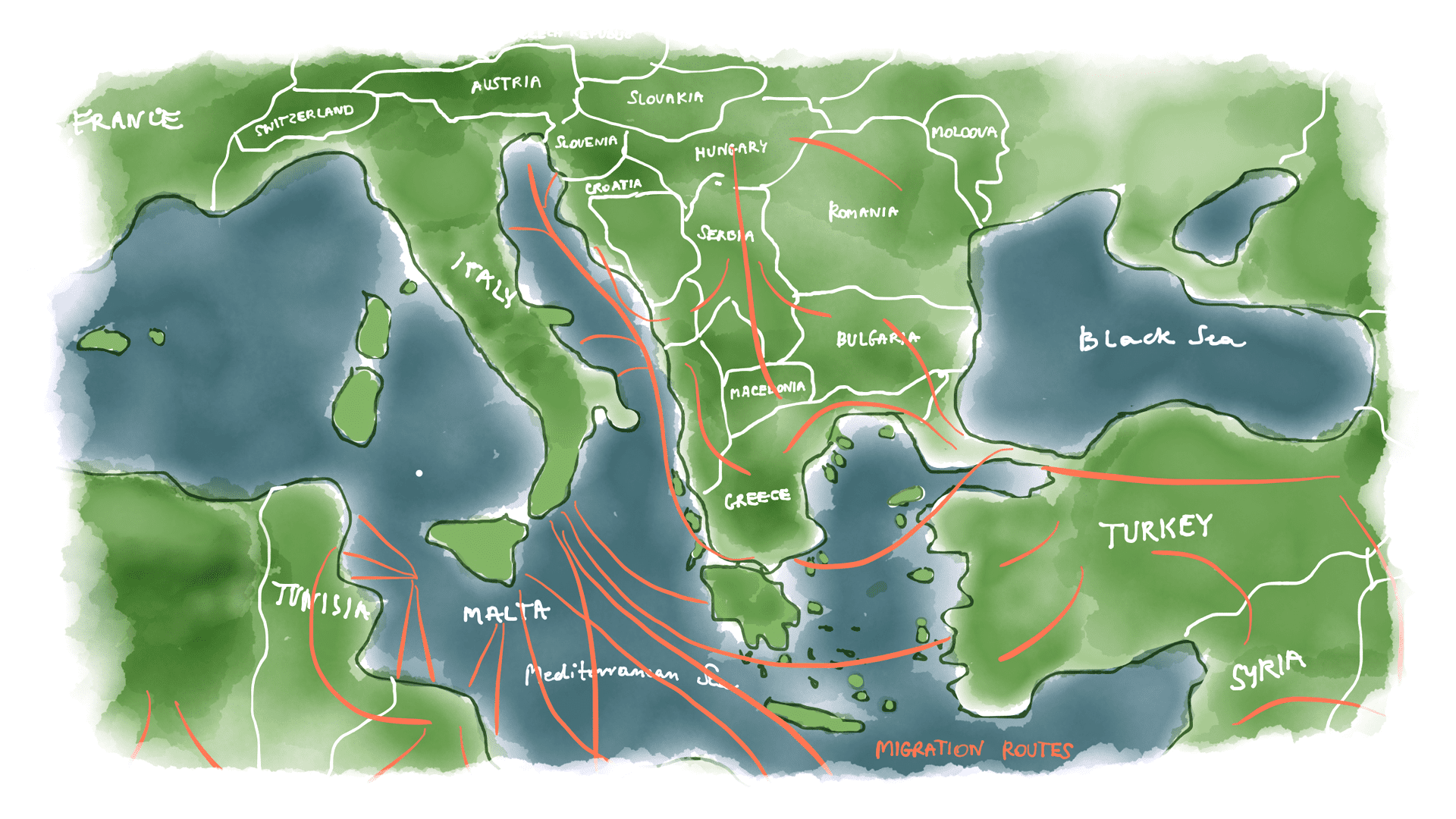

There are many migrant routes to Europe. They lead through water, land and may have different names. According to “National Geographic”, there are two main ones: the East African route and the East Mediterranean route. The first one leads through Libya and Egypt to Italy and Greece, of course by sea. The second one begins in Syria, leads through Iraq, Iran, Turkey to Greece and further into Europe. Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, which manages operational cooperation at the borders of the EU, distinguishes eight migrant routes. Two of them are mentioned above. Additionally, there are three routes which lead through the Mediterranean Sea: eastern, western and central. There are four more: to Apulia and Calabria in Italy, to the Canary Islands, from Albania and through the eastern borders of the EU. The last one is called the West Balkan or simply Balkan route which currently does not exist in this form. In 2015 an unregulated stream of people was going through Europe. It was quicker to enter Austria or Germany from Greece as an illegal immigrant than it would have been using the legal means. According to official sources, in October 2015, 220,000 people reached Europe, mostly following this route. It was the biggest number recorded in any month. In comparison, a year later it was "only" 30,000 people.

In one of the cafes in Thessaloniki, we talk to activists who help people cross the Macedonian border every day. They organize clothes, shoes and food supplies in the city. Then, using their own cars, they take the goods and products to the camp right next to the border. I ask: how do the migrants arrive here? A part of them remains in the vastly overcrowded camps on the Greek islands. Most of the migrants take ferries to the continent and after that they are transported here by special buses. At least that used to be the case.

Previously, also in Thessaloniki, many migrants were camping out in various parts of the city. Idomeni is located just over an hour drive north from the city. There are another five kilometres to the camp from the main road which leads to the official border crossing. The first car I managed to stop is packed with parcels and people. Five seats in the car are occupied by seven people, among them volunteers going to Idomeni. They stop the other car which is going with them. After a quick repack we are driving together. No one has questions. The camp is located just behind a railway crossing. Volunteers introduce me to an Australian man of Greek descent who spends part of his holiday helping migrants. He guides us through the next tents, explains the functioning of this place and introduces us to other employees. Each camp can be described in a similar way: many people in need, not enough hands to help out. You can ask questions and talk but at the same time you have to work. Sometimes people unpack the packages, put them up in a tent, sometimes they distribute water.

Entering the camp for the first time, one can get an impression of great chaos - the place is bustling with conversations, running children or cars transporting parcels and food. However, it is enough to stop at the side and observe for a moment to notice the rhythm. The bus arrives packed with people, volunteers appear, give a number to one person and say that from now on they are a group and must take care of themselves. They will cross the border together. Before they go further, the migrants receive water and food in two tents at the entrance. They can also ask for a blanket or something special for their children. They quickly get something to eat and drink. Satisfying basic needs and providing simple information loosens tension among people which, in turn, helps with the camp’s organisation. The group also has a dedicated place in the tent, so they do not need to nervously check if it is already their time to go. They are waiting. Four large tents offer a chance to seek shelter from the wind, rain and have a bit of sleep. Stress management is a key skill for mastering the situation at border crossings. Idomeni is the best organized camp I had ever visited. We go further. There are two medical points - the Red Cross and Doctors without Borders. Then there are the toilets, volunteers’ barrack and the small office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the body that coordinates international refugee action and the movement of people. One of the groups is preparing to cross the border. They first gather between the tents and then travel along the railway track to the Greek border guards. They wait a moment there and move on to the Macedonian side where a small transit camp is set up. There are some small fences with barbed wire to make sure nobody deviates from the route. I spend the night talking. I ask the migrants where they are from, why they run away, how much they paid, what did they do and what their plans are? One doctor I meet says that he heard he will find a job in Germany. There are also architects, two IT specialists and builders. Men and children are most eager to talk to me. Not everyone speaks English. However, I am not the only one asking questions. There are a lot of them directed at me. The main issue is, if I know what the next stages of the route are, or if the borders are open. I was talking to a migrant architect about Poland for a long time. He was curious whether he could be employed in my country. Soon I'm joined by two sisters, aged 16 and 13. We talk for a long time about their route. They lived in Turkey for six months with their little brother and parents. They are from Syria. Two days ago, they sailed from Turkey on a boat. Someone joins the conversation and says that his boat capsized, but fortunately it was not in the open sea and everyone made it to the shore. The second time it was successful. The conversations about boat crossings trigger biggest emotions. This is the most dangerous (and the most expensive) part of their journey. Finally, the sisters ask if they can stand next to me. They are afraid that something can happen to them at night. Who is supposed to protect them? Family, friends and good people, who else? They are not even registered, so no one is responsible for them. If they have their documents, they do not matter much. In their desired destination (they go to Germany) these papers will only confirm their background. Nobody wants to register them either, because then a formal responsibility would appear. Without doing it, the problem is smaller.

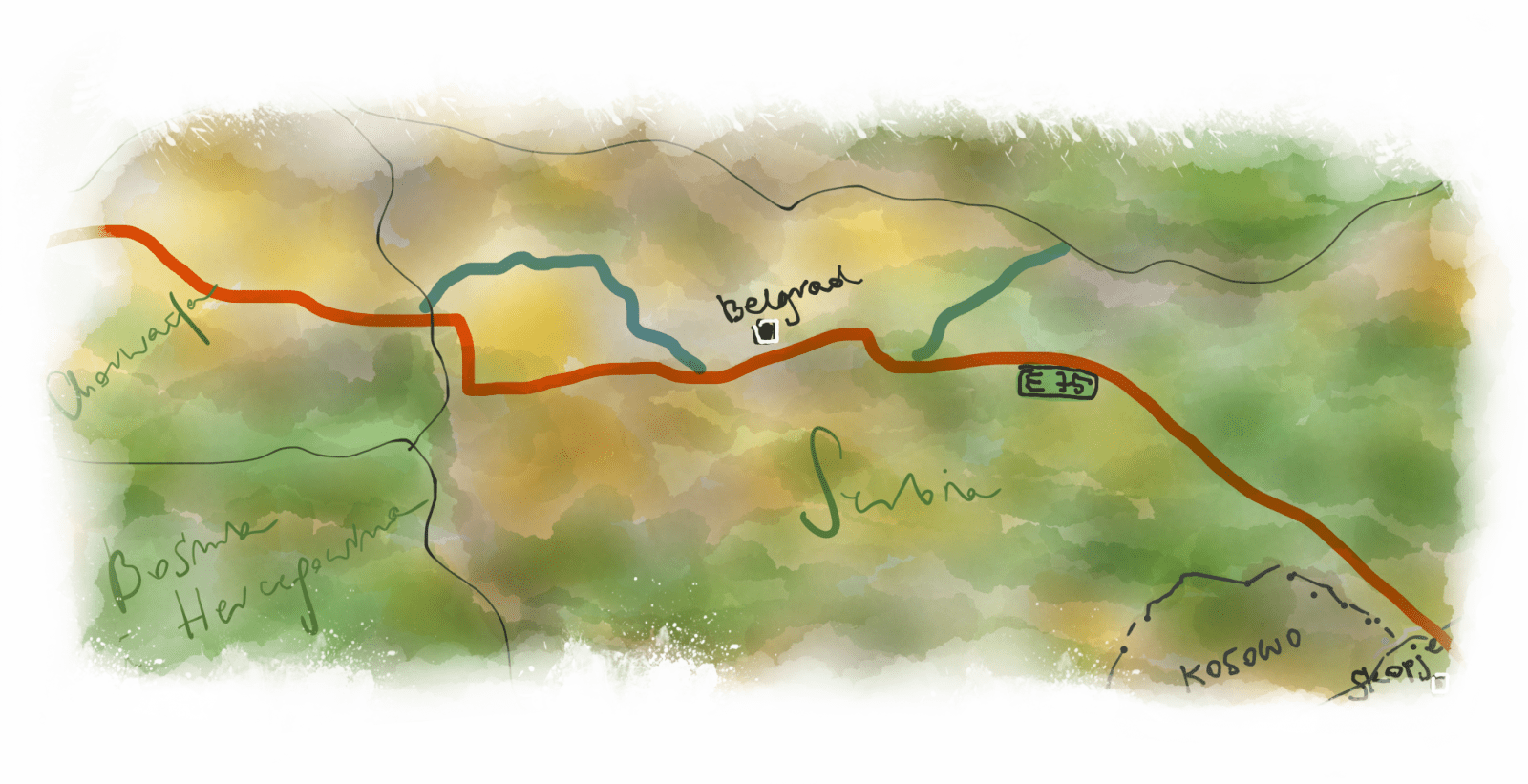

After moving to the Macedonian side, the migrant groups board a train. It will leave when it is filled with people. The train has its first stop at Gevgelija station, a few kilometres from the Greece-Macedonia border. It is immediately approached by some local merchants. Already in Idomeni, right next to the camp, several selling points appeared. They offered more than was available in the camps, for example Coca-Cola or hot dogs. The prices are twice as high as in the shops. Here, the retailers sell SIM cards (most desirable product), drinks and snacks for the journey. When the train leaves, they hide in the shadows and wait for the next transport. You still have to pay for the trip. It was free at first, then it cost 5 euro. Now the Macedonian government charges 20 euro per passenger. The journey throughout the country takes about five hours and the train arrives at the station in Tabanovce. In Skopje activists and NGOs organise themselves. In the warehouse, not far away from the city centre, I meet Sandra. She oversees the collection of things for refugees which are sorted and packed here. There I can hear one figure - 6,000. So many people cross the border every day. This is confirmed by the Greek calculations. Other facts are also correct, such as the one that the boats are often sailed by refugees themselves, who are trying to earn their living this way. Their lack of experience is also a common reason for capsizes. In the morning I come back to Tabanovce. I enter the station when a train terminates its journey. The Red Cross leads a temporary camp in the building - the migrants do not spend too much time there, though - they only stretch their bones, eat meals and drink water. They can sleep for a while. But I do not find anyone in these tents. I see a room full of clothes that could be taken by people in need. There is also a point for those in need of medical help. There I find a sick Syrian man. He is about 30 years old and has a big leg problem. He tries to rest before he goes any further. Nobody stays here for a long time. After a short break, migrants move on. They are heading for the border with Serbia. There are still a few more kilometres to go on foot. I join a group that is headed to the border. They are reluctant to talk, but I know they are coming from Syria. They tell me what they had to sell - a car, a house, how many thousands of dollars they left in Turkey. There is not much left. When asked about the house, the children talk about the garden. It turns out that the whole group is a family. I reach the border and turn back to go to a border crossing point which I can use. Before I do that, I see that they are already going further.

A taxi can take 4 people. This makes EUR 40. Local drivers are keen to take people exhausted with the journey and the long walk through the border to the point from which buses set off to the Croatian border or to Belgrade. A family pack costs nearly PLN 200. Many people go for this option. Perhaps they negotiate, though drivers don’t behave nicely. Cars move around aggressively, honking. A lot of tension in the air. The road is narrow. Good, fast and easy profit. Soldiers seem most relaxed. Rifle barrels idly touch the ground. They look around if everyone goes in the right direction and don’t change the route. Taxis can pick people up at the control point; behind the soldiers we can see the border zone where only cars with permissions can enter. They are not smugglers. They just use an opportunity. One of the drivers asks me if I’d like to go straight to Belgrade. I can hear him offer this destination to others, too. Buses wait between Miratovce and Preševo. Drivers wait for their turn. Nearby shops are besieged. People swarm and buy hastily before they move on. Most of them go directly to the Croatian border.

The Belgrade Main railway station. I change trains here to reach another border – with Croatia. When I walk out of the building, my attention is caught by two tents. I enter a park and see more of them. The park is called Bristol. The centre of the Serbian capital. Within the park – a small village. There is an information point, multi-language signs, two tents with food and drinks. The tents are shared by everyone. A board is resting against the point. The first information: “Croatia open”. It’s a response to the main question: which way to go now? Only a couple of weeks earlier, refugees would go north, to Horgoš, to the Hungarian border. Today, they go east – to Šid.

In August 2015, images from the Keleti station got around the world. It was the culmination of the refugee crisis in the media. The Hungarian government has been conducting the anti-migrant campaign for a long time, threatening Hungarians with refugees taking their jobs. A few posters are still hanging in the capital. It’s much easier to intimidate people with something that is invisible. Nobody predicted the solidarity generated along the chaos at the station. Activists organize illegal shelters. People spontaneously bring clothes and shoes. Trains leave on time from the Keleti station. The police arrange travellers in lines. It’s relatively peaceful there now. Journalists from all over the world also came to Hungary. On the walls of the subway entrance in front of Keleti there are two inscriptions: "Welcome to Budapest" and "I want to go to Germany". I see a girl playing next to them. When she saw the camera, she moved away with a smile that clearly said she did not want to be caught in the frame. I took a picture when she left. After a while a journalist from Australia came up. She forced the little girl to come back and pose for the photo. As children would have it, she listened but the smile disappeared from her face. There were no parents nearby, no one who could intervene. One photograph can change the whole narrative - just like the one of a dead boy washed up on the beach in 2015. The Röszke camp, on the other hand, was very chaotic. Help was only provided by NGOs. Scared people pushing into buses. Screaming and cramming everywhere. Children being handed from one person to another. There is a lot of talking about the police being aggressive. It’s just more nervousness and stress than real violence. Back in September 2015, the migrant route still led through Budapest and further to Austria. In the meantime, the 'wall' (or, rather, the fence with barbed wire, has been completed) and the Hungarian government has done everything it could to stop the refugees. Border crossing points exist, but the stream of migration has changed its course - now it goes through Croatia.

It rains heavily in Bapska. Afar, we can see the row of tents resembling a huge snake. The EU flag is waving next to the Croatian flag. For the second time on the Balkan route – but now there are only EU countries left on the way to the goal. When I ask about it, I hear two names: Austria and Germany. Most people opt for the latter. They heard good things about Germany – first of all, they believe to be well-received there. They ask about Poland – how people live, what kind of country it is, what currency we have. I ask about their emotions. Are they happy to be so close to their destination? Yes, they reply, but they are also anxious – what's next? They are scared to be sent back. I try to diversify my questions. Asking someone who has been marching for so many kilometres, having left everything behind, about how he or she feels – seems infantile. However, it helps break the barriers and open up. Out of exhaustion and sometimes reluctance to talk, stories emerge. Groups travel by bus from the border towards Opatovac. The camp looks more like a military one rather than a refugee camp. Numerous guards. If it wasn't for the humanitarian help tents outside, it would be hardly noticeable. Policemen invite me to their tent. After 10 minutes of cheerful attempts to establish how the Polish language is close to Croatian, they pass and go back to their interrupted conversation. It's only possible to enter the camp in the company of a manager – through two tents. Except for me, two more TV station crews are waiting there. It's 8 o'clock – the manager should come at 10. I enquire about further part of the route: from here, by bus, to the nearest train station and then by train to the Slovenian border. While waiting, I attempt to count how much it would cost to get from Turkey to Germany. The data I have are totally contradictory but I'm trying to establish the cheapest charge per person:

And this is just the cost of the transport itself. When it comes to confirming these costs, it is most difficult to establish any expenses the migrants must cover in Turkey. I tried to confirm one sum but everyone gives a different amount. When asked how accurate their data is, the UNHCR staff reply that they "do their best". I am talking to a father of two. Just two days ago, they were still on the Turkish side. "It took forever", he says. "All the time I clung to them, fearing that the boat would capsize". This is the toughest moment of their journey. They arranged everything in a few days with the smugglers. Two hours later they stood at the station and left by train in the direction of Harmica. Police are nervously trying to prevent people from taking pictures. But watching is not forbidden so everyone can stay at the station.

At the railway station in Vienna it is almost midnight. The trains are no longer running, everything is closed down. Several dozens people try to fall asleep on the benches and empty restaurant chairs. The first trains, which are already regular and not dedicated for the migrants, will depart at around 5 a.m. A group of younger men talk at one table. They came through Slovenia, crossing the border in Dobova and Šentilj. They have already arrived at their destination. The last train will take them to Germany. We can see a smile on their faces but also terrible fatigue. I ask: what now? Nobody can answer.

Najostrożniejsze szacunki mówią, że drogę bałkańską do dzisiaj pokonało: