The minimum wage in Brazil is around 215 euros per month. But according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, 60% of the country’s workers (54 million people) receive salaries lower than in 2018. Now imagine the Amazon Rainforest and its vast green territory. One single truck carrying timber of Ipê tree is worth 65 thousand euros, and it takes only two or three people to work. Logging is an absurdly profitable business in Brazil, and the gains are even higher if it’s done illegally, which means not paying for taxes and documents.

Francisco is 40 years old and has four kids. He never went to college, and by the age of 11 he started working in the illegal gold mine with his father, who was killed by other miners one year later.

He grew up in mining and had his first son when he was only 16 years old. Francisco says his whole family worked in the illegal gold business, so he had no other options. However, ten years ago, he decided to change his life. The lack of education and opportunities took him to another outlaw activity in the forest: illegal logging.

„We are not destroying the Amazon because we only take a few trees in each area we go to. We need to work, and we are not lazy like the indigenous men” Francisco da Silva says.

Indeed, logging works differently than other activities like land grabbing or mining. Loggers usually look for specific species like Ipê, Mogno, Angelim, Favero, Cumaru, etc. In theory, they do not need every single tree they find, but it does not mean their work does not bring high impacts to the forest. To extract the wood trucks and tractors are necessary, and of course, they produce a path of destruction. Some animals disappear, and surrounding communities are also affected. In many cases, this activity is also related to corruption networks involving several parts like politicians, police and environmental agencies.

Another problem is those illegal loggers look for the “good trees” and it does not matter if they are inside of private properties, national parks or indigenous territories. The Uru-eu-wau-wau land is a huge green island in the middle of deforestation and endless cattle fields. It means the indigenous lands are the main target for loggers of that region.

Francisco da Silva: „Plantations and cattle need investments and take more time to produce a profit. Logging is easier and faster because the trees are already there. You go and take them.”

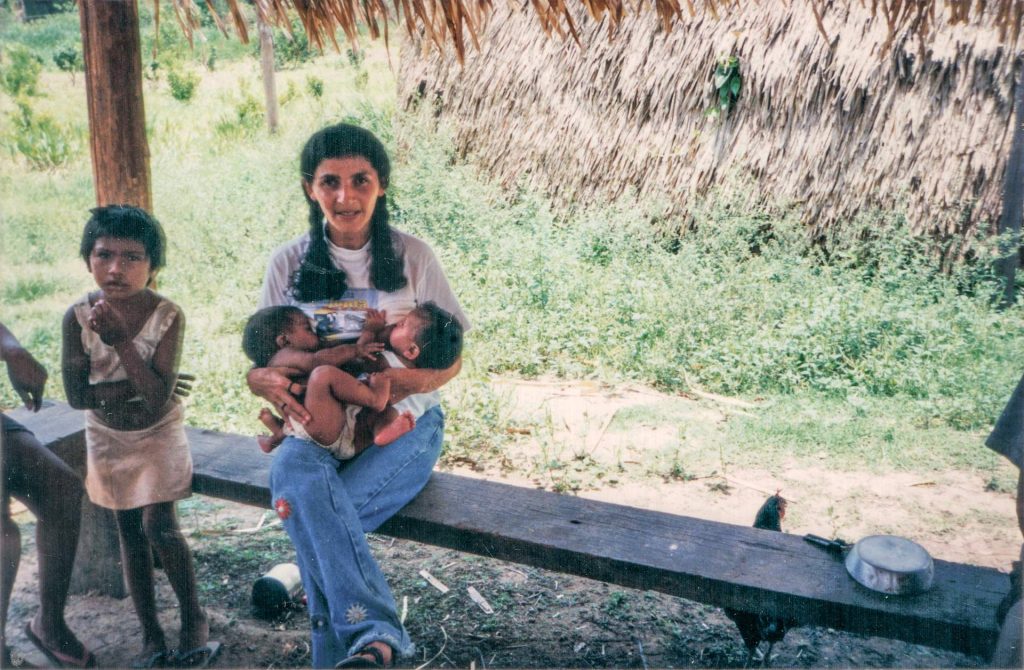

The complex Amazonian scenario of large territories, lack of human and economic resources and complete failure to enforce laws produce a chaotic opportunity to criminals. According to the Federal Police, 90% of the exported wood from the Amazon is illegal. In the meanwhile, the Uru-eu- wau-wau people are using bows and arrows to fight not only to protect their land but also to save the animals, nature and their own lives.

Behind the fires, there is a lucrative business.

*Francisco da Silva is a fictional name. He only accepted the photos and the interview if his real name wasn’t revealed