Chapter 1

The path to the communal forests

On an early Sunday morning, an open kitchen of one of the houses in Santa María Yavesía smells of freshly prepared meat for tacos that will soon be served to us for breakfast. Hungry, a few locals sit at the only table on the terrace. Sipping their coffee, Eliel Cruz Pérez reminisces about their battles for the biodiversity of 9,000 hectares of their pristine forests.

"Every day, at four in the afternoon, five men drove up in the car to the forests and brought back the villagers who had been there since the previous day. There were days when we had so little to eat, we put a few potatoes into the ashes, and that was all we ate. But we kept on patrolling for three years," he recalls times when Yavesía’s villagers were trying to protect their environment from logging by the Fábricas de Papel Tuxtepec that had concessions from the federal government between the late 50s and mid-80s.

It was back in 1910 when peasants across Mexico, led by Emiliano Zapata in the South and Pancho Villa in the North, started a revolution with a slogan: Tierra y Libertad (Land and Freedom). They overthrew the dictator, and even though years of civil unrest followed, the events lead to the first agrarian law that brought the land back to the people. One of the milestones in the land ownership and protection that resulted from the Mexican Revolution was Article 27 of the Mexican Constitution from 1917. It also stated that the communities are considered legal entities that can have control over their land and its use. Mexico considers two types of land for community management: ejidos or agrarian communities.

Although indigenous peoples had rights to their land since the land redistribution after the Revolution, economic expansion after World War II resulted in the federal government treating forests as public resources. In exchange for a stumpage fee that was below the market value, the government awarded concessions to two forestry companies in 1956, Fábricas de Papel Tuxtepec (FAPATUX) and Bosques de Oaxaca. The decrees only expired in 1983. Other activities that were harmful to the environment were happening in the mines, often owned by companies with foreign capital.

"If villagers saw people in the mountains who were not from Yavesía, they would report it to the municipality. Afterwards, the bell was ringing to announce an emergency meeting, and a decision was then made to go and patrol the next day so that they do not take away our wood," says Eliel.

"I remember being a little girl and preparing tacos for my grandfather before he went to patrol the forest," Eliel's sister Rosa adds. "They did not bring any armament, it was all about their presence there." No one was paid for patrolling. And the tacos Rosa used to prepare had no meat, but potatoes.

Broken promises of development

The situation of Santa María Yavesía was not unique in the region of Sierra Juárez, situated north from the City of Oaxaca, also referred to as Sierra Norte. Deforestation and mining, both had a similar, negative impact on the environment and people’s lives.

For decades, indigenous communities watched as their forests disappeared, their waters were becoming polluted, their inhabitants were getting sick, all while their communities were barely if at all, benefiting economically. Even though such was the promise from the companies and the government, both driven by economic growth as the main priority.

"They did construct the road to bring wood from Ixtlán to Oaxaca City, but they never discussed the logging activities with the communities. The only thing that the company created for the community was employment. Otherwise, they did not leave any utilities once they left," says Mauro Hernández, responsible for the community company making furniture in Ixtlán de Juárez, capital of the region of Sierra Juárez.

In Santa Catarina Lachatao, the community firstly agreed with the logging activities of the company from outside until the exploitation of their forests became too much and they got too greedy. "Our elderly were saying that the company had certain trees marked to cut them down. But, because they were paid according to the volume they delivered, they cut more," Juan Santiago from Lachatao remembers. “ The exploitation of the forests was causing scarcity of water."

In Capulálpam de Méndez, people observed that water in the creeks became polluted by mercury used to mine gold and silver in Natividad, a village that lies in the territory of Capulálpam. Miners who spent years working in the mine also had poor health. Villagers stood up against the company's interests.

Extra step

Nearly half of all the world's forests (46%) have been lost due to deforestation since human civilization started, according to a study published in Nature in 2015. In only 50 years, 17 per cent of the rainforest had been lost.

In Mexico, vast deforestation was going on for decades. In the second half of the 90s, more than 800,000 ha per year were lost, FAO informs. The situation is changing, in 2018, the country lost 262,000 ha of natural forest according to the Global Forest Watch.

The deforestation is mostly due to the change of the use of land from forests to agricultural land. Commodity-driven deforestation for mining, oil and gas production, together with forestry, wildfires and shifting agriculture are the most common reasons for deforestation around the world. Corporations wanting to make a profit exploit natural resources, very often with a blessing from the local government as well as governments of the countries where the goods will be exported to. But, at the end of the day those same corporations pass on the blame, pressuring us - individuals, to change our habits to avoid the disaster that the climate crisis might carry.

In Oaxacan communities in northern Sierra Juárez, such broken promises of development led to a strong social movement in the mid-80's. Being left with a destroyed environment, Oaxacan indigenous communities united to gain back the rights to their forests through discussions and negotiations with the government.

Apart from doing things like growing organic food and separating trash, no matter how remote the villages are, they also made an effort to regain control of what matters to them - the place where their ancestors came from and its natural resources. The region where the villages we visited are located, has shown a 3.3% expansion of forest cover in its pine-oak forests over 20 years.

The place we inhabit: unity with nature

"When will you build the road to Lachatao," I ask when Ali Santiago Hernández is driving us up the bumpy road to his village, located more than 2000 meters above sea level. The village below Lachatao is constructing a new concrete road within a new government scheme that gives money directly to the community, and people from that place have to build the infrastructure projects themselves. Apart from the new road, employment for a few villagers is also guaranteed.

"We do not want the concrete road. It does not let the land breathe," he replies.

Perhaps that’s an extreme decision made by the community, but it represents magnitudes how indigenous peoples in Oaxaca perceive their relationship with the environment. They see themselves as a part of nature, not above it. They co-live with their environment. For generations.

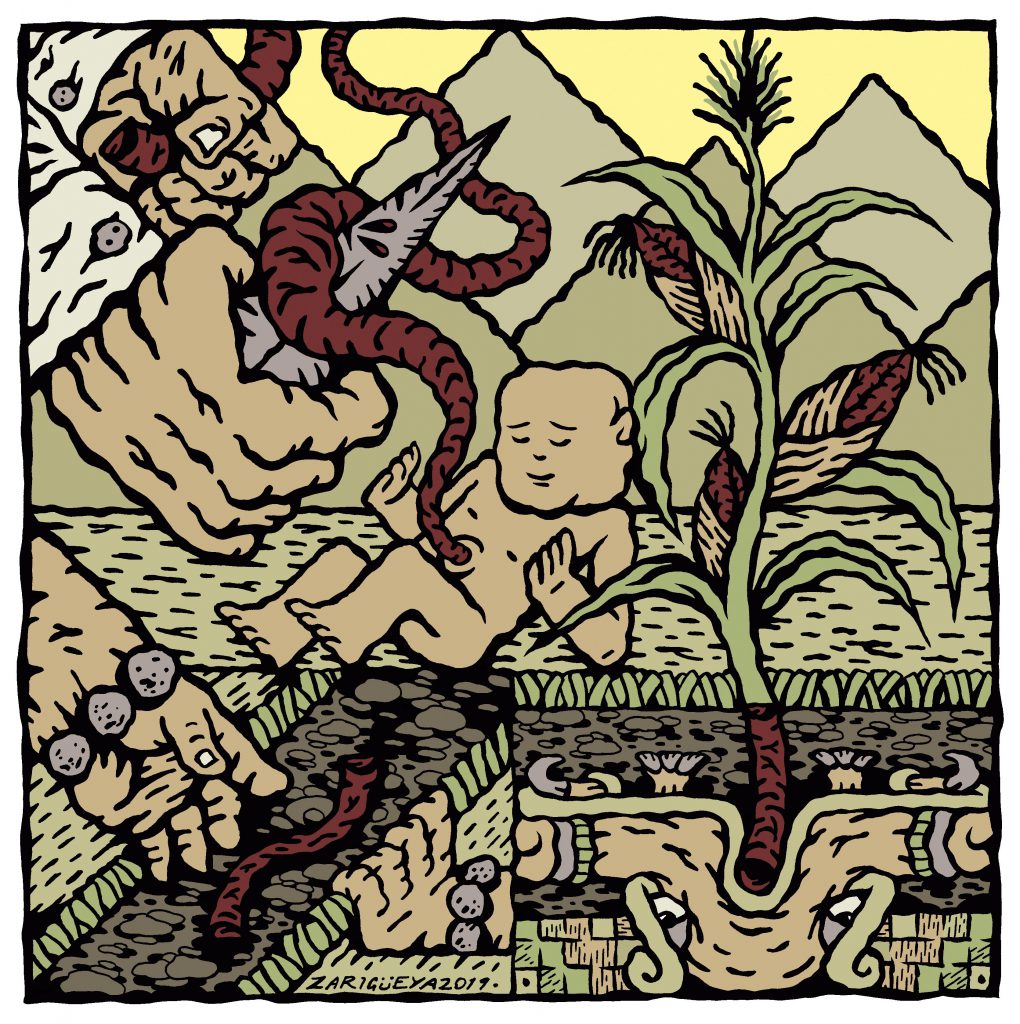

"When I was a kid and went to the forest with my grandfather, he used to tell me: "Do not make noise or you will wake up the owners of the mountains. We will only get the wood we need, and we go back." Through these kinds of legends, myths and rituals, we learned how to co-live with nature," Fernando Ramos Morales, a research professor from the University of Sierra Juárez, explains.

In all the villages, rituals, including offerings for Mother Nature, are essential at important days of the year, usually linked to the harvest or celebrations of different elements of nature and historical moments of the lives of communities. Not so long ago, Zapotecs still buried the umbilical cord of a newborn baby in the village, to stress the connection they have with the place where they come from.

"Here, we do not see nature as a business opportunity, as a natural resource that needs to be exploited in an irrational way. We live in harmony with the environment. We respect nature and all the ecosystems," explains Francisco Luna García from Secretariat of Common Goods in Ixtlán de Juárez. He is responsible for the territory that belongs to the municipal town in the region.

The Sierra Juárez region is one of the most biodiverse places in all Mexico, an already mega-diverse country. In general, indigenous people inhabit only 22 per cent of the land around the world, and this land is home to 80 per cent of the globe's biodiversity.

"The territory was here first (before us). When we came here, we were like a part of the fauna of the place," Jaime Martínez Luna, one of the Zapotec intellectuals explains. "It is necessary to know the soil where we live. We need to know how to use it, but for the benefit of us all."

Connection to the land they inhabit is the number one pillar of the way of life that the majority of Oaxacan communities follow. The legitimate governance system called uses and customs (usos y costumbres) covers two pillars: a general assembly which is the maximum authority in the communities, a system of cargos and collective work. The fourth pillar but of same importance are celebrations.

All these pillars compose the way of life Oaxacans call comunalidad - communality. Communality is what allowed local communities to become an exemplary region in terms of sustainable forest management in the world.