When Hovig Dangourian heard the sound of suicide bombers in the Saadallah Al-Jabiri Square marketplace, one block from his home in Aleppo, Syria, he and his wife pulled their three kids to the floor. “We were quiet, like mice. It felt like time had stopped,” Hovig remembers. “We didn’t know what was happening, but the only thing I remember is being scared –– scared for the lives of my children.”

Hovig, a psychologist-turned-entrepreneur and a third-generation Syrian, still recalls the dust clouds rolling through their street in the aftermath of the bombing that shook their house, which was as powerful as a 7-Richter scale earthquake. It is when Hovig and Isabel decided to get out as soon as they could.

Together with his brother’s family, they fled their home and their war-torn country to find a safe haven in Nagorno-Karabakh, a disputed territory in the South Caucasus. Driving in their black Kia, the 1600 km route took them through Turkey, Georgia, and Armenia — they encountered dozens of checkpoints, fearing their lives.

With recently renovated neighbourhoods, green parks, and a vibrant bazaar, Stepanakert, the capital of Nagorno-Karabakh, felt like a quaint little regional town. Kids played in the parks after school, couples had coffee at one of the little cafes, and the women at the bazaar made the region’s famous herb-bread chat away, while a hungry line waited their turn.

Surrounded by mountains and lush, fertile fields, you could understand why the Dangourians at that time chose to resettle in Nagorno Karabakh, even though two nations have been fighting over it for decades, if not centuries.

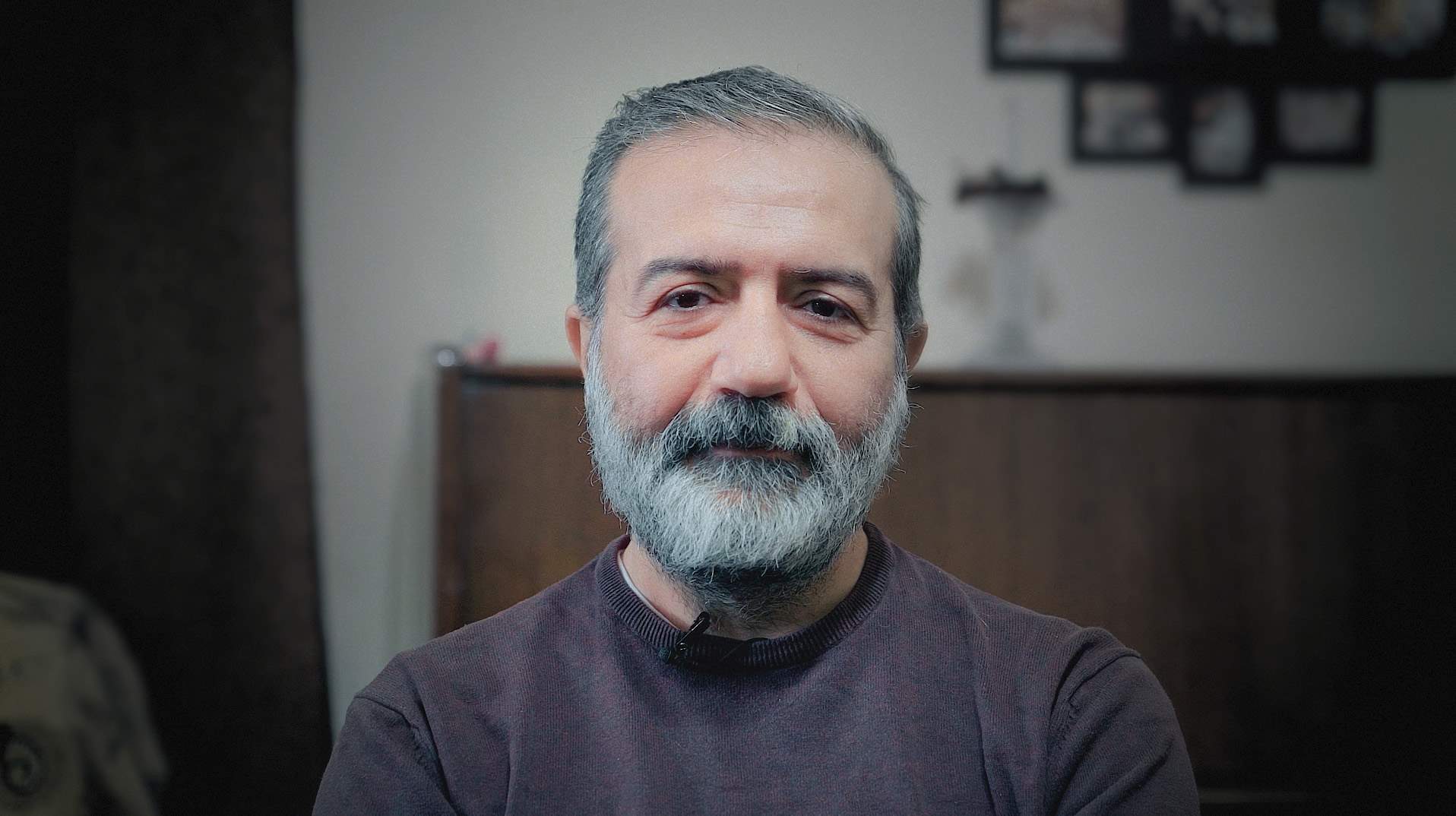

About one year ago, we travelled to Stepanakert and met with the Dangourian’s. Chatting with us in September 2019 in their newly-opened fast-food cafe, adorned with red flowers outside the windows, centuries-old stone walls, and vintage memorabilia, Hovig — a tall man with a proud posture — and his wife Isabel — her large dark eyes piercing through, a small nose piercing, and her black hair held up with a colourful bandana — explained that they finally felt safe.

“Our three kids walk to and from school every day, and I know I don’t have to be worried. Stepanakert is a quiet and friendly town,” said Isabel as she was pouring us some freshly brewed Syrian coffee — a dark roasted and finely ground coffee with a hint of cardamom added at the end of the brewing process. She didn’t know then that the war would erupt again, but they weren’t afraid of it either.

Two routes lead from Yerevan to Stepanakert. A recently renovated road — partially paid for by Armenia’s diaspora through the Hayastan All Armenian Fund, passes by Armenia’s pride, Lake Sevan. With the recent peace deal signed by the two countries, this route will no longer be operational.

Over 5 million people outside of Armenia identify as Armenian diaspora, while Armenia only has around 3 million citizens, and about two-thirds of the diaspora lives in the US and Russia. Rebuilding Nagorno-Karabakh has been highly supported by the diaspora, including adding a new highway to shorten the trip.

The route is both mesmerizing, as eerie. The “dead-zone” — with high, bare mountains where gold is mined, narrow and steep passes — is where Armenia’s cell-services stop. Deserted Azerbaijani villages along the route show the gruesome impact of the war from almost 30 years ago.

Nagorno-Karabakh has been in a complicated and violent conflict stretching over almost three decades. Internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan, the territory is de facto governed by Armenia after a bloody war in the early 1990s. The fall of the Soviet Union led to several different civil wars in the vacuum of power, and the South Caucasus was prone to conflict due to its complicated borders, ethnic minorities, history, and mountainous landscape. The struggle over Nagorno-Karabakh is similar to the other conflicts in the region: different parties claim ownership over the region.

Although several different violent conflicts have erupted over the territory since the war in the 1990s, nothing has been as significant as the current – almost two-month-long – war that is waging over Nagorno Karabakh.

Fighting began on September 27th and has left hundreds, if not thousands, dead. UNICEF reported on October 28th that over 130,000 people have been displaced since. Azerbaijani authorities said that 91 people have died and 400 have been wounded, while Nagorno Karabakh authorities stated that the fighting has claimed 116 of their troops and 45 civilians. Russian authorities, however, have stated that according to their information the death toll is likely much higher, at around 5,000.

Under the recently signed peace agreement between Armenia, Azerbaijan and Russia, Azerbaijan will hold on to areas of Nagorno-Karabakh that it has taken during the conflict. Armenia has also agreed to withdraw from several other adjacent areas over the next few weeks. Russian President Vladimir Putin said Russian peacekeeping forces will be deployed along the contact line in Nagorno-Karabakh and within the corridor that connects the region with Armenia.

But for Hovig and his brother, Vrezh, moving their families from war-torn Syria to the unrecognized Nagorno-Karabakh back in 2012 made perfect sense, for several different reasons. And they weren’t the only ones.

Born and raised in Aleppo, the Dangourian family was part of the city’s tightly-knit Syrian-Armenian minority, a community which evolved around a sustainable ecosystem — including schools, churches, grocery shops and charities. “We took care of each other. If someone couldn’t pay for school, the community took care of it. If you didn’t have a family to help you in your old age, the community would take care of you. No one was left behind,” Hovig recalls proudly while sitting in his living room in Stepanakert. A few pictures on the wall show their family in a vibrant and lively Aleppo.

Although Armenians have lived in Syria’s current territory since the Byzantine era, most of the ethnic minorities settled in the country between 1914 and 1923, when they were forcefully removed from Turkey during the Armenian genocide.

Hovig’s grandfather was only a child when he endured the harsh trek, losing several family members along the way to the Syrian desert of Deir ez-Zor. His mother even decided to leave Hovig’s grandfather’s infant brother with a Syrian family in a village they passed, worried he would not make it otherwise. Decades later, Hovig’s grandfather ran into his brother at the local bazaar — it was as if he looked into a mirror.

The Syrian-Armenian communities thrived in their new home country. Hovig tells us proudly about the several companies his father had set up, two of them which Hovig ran, including an auto parts company, and one which his brother ran, a wheat farm. The Dangourians, an upper-middle-class family, often took trips to Bali and Europe, and they still own an apartment in Bali which they rent out.

“We lived in Aleppo in a beautiful, large apartment in the centre of the city,” Hovig says, seated at a table in their cafe, while his wife is taking a few orders behind the counter. She joins the conversation, nostalgically describing their former home to us –– from their antique velvet furniture to their hardwood floors to their view of a park full of lavender in which she’d walk for hours each day.

“I can’t smell lavender anymore,” she says fighting tears. “I won’t do it, I won’t even come near it.”

For Isabel, fleeing their home in Aleppo and resettling in Nagorno-Karabakh has been difficult. She explains that she grew up quite wealthy, laughing at how she didn’t even know what the inside of her walk-in closet looked like: she had maids picking out her clothes for her. “I was spoiled,” she continues, “and look at me now, learning how to make traditional Syrian food in a small cafe.”

Syria, engulfed in a violent civil war since 2011, has made international headlines with what began as a peaceful uprising against President Assad, to being one of the bloodiest conflicts in the world today. After nine years of conflict, it’s the world’s largest humanitarian catastrophe, with over half of all Syrians displaced by the war: 6.7 million have fled the country since 2018 according to UNHCR, and the Dangourian family are among them.

Most of the refugees live grim and harsh lives in camps along the Syrian border in Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan. Others have made it to Europe, with over 3.5 million Syrian refugees trying to pick up their lives again.

The stream of refugees over the past few years to Europe has turned immigration into a heated social and political issue. On the one hand, many voice support for taking in refugees, but on the other hand, anti-immigration groups have become emboldened, spreading falsehoods about the impacts of the refugee streams.

But what is often forgotten during the debate on refugees is that not everyone fled to Europe, and those who did, often did not have any other option.

For the Dangourians, who were smart enough to withdraw their savings for a second house when the protests started, living in Nagorno-Karabakh was as close as they could get to living a “peaceful” life in a place where they are welcome. Now, that the war has started here as well, they have not changed their minds about their decision.,

Armenia, with less than 3 million inhabitants, has taken in over 22,000 refugees UNHCR says, since the start of the war. That’s about the same percentage as Germany took in, with 770,000 refugees — according to Germany’s Federal Office for Migration and Refugees as of December 2018 — and a population of around 82 million. More than half of the refugees have decided to stay and call Armenia their new home. The impact can be felt throughout the country, with an influx of new restaurants, goldsmiths, and other craftsmen opening their shops.

“By now, many Syrian-Armenians feel at home,” explains Armenak Tokmajyan over the phone. Tokmajyan is a researcher at the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut, focusing on borders and conflict, Syrian refugees, and the state in Syria. Moving from Armenia to Syria when he was a child, and back to Yerevan when he was an adult, Tokmajyan knows both professionally and personally the routes the refugees have taken.

“When I talk to Syrian-Armenians for my research, they tell me about the economic challenges they face, but also how much they love Armenia: the wide streets, green parks, being able to walk home safely late at night as a woman,” Armenak says.

Although the refugees have found a home in a place which was called their ancestral homeland for centuries, Armenia has struggled after the fall of the Soviet Union to become an economically independent country. With closed borders on the West with Turkey due to the disagreement on the roots of the Armenian Genocide and the war between Armenia and Azerbaijan, to closed borders on the East with Azerbaijan as a result of the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh, its only trade routes run through Northern-bordering Georgia — which only recently started to become economically viable itself, and Southern-bordering Iran — plagued with economic sanctions and restrictions.

When the bombs hit close to home, both Hovig and Isabel knew they had to flee. Having travelled to Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh for their honeymoon in 2004, and being of Armenian descent, the choice to settle in Stepanakert was quickly made -even though the territory has been disputed for centuries.

“I refused to go to a camp and be dependent on other people,” explains Hovig, adding that his father taught him, “it’s the man who makes money, not money that makes the man.” Also, his mother taught him to be a proud Armenian. “Armenians are hard-working people –– an Armenian won’t beg, but will be able to earn his living with hard work, to make bread out of stone.”

But it wasn’t an easy process. “Our kids were young, they had learned patriotic songs in Arabic in kindergarten praising the Syrian army, the president, the country,” says Hovig. His son Levon was eight when they fled, his daughter Arpi was four, and their smallest son Kevork was only a baby. “When we reached checkpoints, and our kids would start singing patriotic songs, we panicked.” It was the first and only time that Hovig shouted at his kids, to make them stop singing. Levon still doesn’t want to recall the events, and Arpi says that memory makes her really sad.

When Hovig and his family travelled to Nagorno-Karabakh, they didn’t know what to expect. Exhausted by a dangerous journey, they rented the first house they could find just outside of Stepanakert. It was poorly insulated, with cracking walls, and rotten wood floors. Isabel cried for months, her son cried for months, longing back to the home they once had.

“First it was one month, and we would return, or we would go to our house in Bali, then it was ‘oh, let’s stay a few more months,’” says a frustrated Isabel. “We were going to help Hovig’s brother and his wife settle and set up a farm, but we wouldn’t stay.” But several years later, Hovig and his wife are still in Stepanakert.

“My laundry was still laying around our bedroom in Aleppo, I hadn’t cleaned it up because I thought we’d be back soon,” laughs Isabel. All they took with them we’re a few coins, the clothes they were wearing, and an old card for an entertainment centre for the kids in Aleppo.

Isabel has made peace with the decision, she says, as she shows us how to make a famous Syrian sandwich with cured meat and fresh herbs. The kids were safe, they went to a relatively good school, and took several private classes after school.

Just one block from their new home, the family rented a room for their kids to do their homework. Arpi, now a bright 11-year-old who aspires to become an astronaut or doctor, walks us to the little, white-walled basement, where books, pens, and notebooks cover the tables. Levon, now 14, sits shyly on the bed, hiding his face from the camera. He doesn’t want any pictures taken of him. “When I was in Syria, I had taken some photography classes, so I can’t have pictures taken of me now. I don’t want to remember our lives here in Stepanakert,” he says.

For both children, life in Stepanakert has been difficult. Both say they don’t really have any friends, except for their mom and dad. Levon can’t wait to move abroad for his studies. His sister feels the same. “There are a few girls in my class who are nice, but they don’t really know anything, and I can’t trust them,” says Arpi.

The question of why they had chosen Nagorno-Karabakh to settle in, a region riddled with conflict and a looming erupting war, is something the Dangourians have been asked frequently.

To Hovig and his brother, the answer is clear: They wanted to move back to “their ancestral homeland,” a place where people understand war. When we ask them how they can feel safe, they don’t blink an eye: “war between two different countries is very different from a civil war in which you don’t know who your enemy is,” Hovig explains, saying he would proudly fight for Nagorno-Karabakh if a war with Azerbaijan would erupt. And while many have fled the region since the war erupted, Isabel and Hovig have stayed behind, providing food for those who need it.

“During the Arab-Israeli wars in Syria and in 1982 during the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, we were there. And after, when we fought the Israelis, we didn’t think of migrating,” Hovig explains. “It was our second homeland, and it would be unthankful to think we moved out because of war. We did not take off because of war, but because of the fratricide. Meaning it wasn’t a foreign threat, but because of brothers being unable to come to a common ideological consent.” And that’s the same reason he wasn’t worried about a possible war over the region he’s now calling home again.

Growing up in Aleppo, the Dangourians were often reminded of their people’s history, traditions, and pride. At home, the family would speak Armenian, and at the bazaar, at school, in the shops, they would communicate in their ancestral language. The impact of the Armenian Genocide was felt throughout the generations. “I almost felt that it was my duty to return one day to Armenia so that the sacrifice of the victims of the genocide was not in vain,” Hovig explains while we’re looking at the pictures of his family back in Aleppo.

He also mentions that being a minority in a country isn’t always easy. While Isabel initially wanted to move to their apartment in Bali, for Hovig this was a difficult decision: they would, yet again, be a minority. “Being the third generation of survivors, we were tired of living within a small diaspora community, I wanted to return to our roots, to the homeland,” he says, referring to Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh.

Even though the family discussed moving back to Syria in the first few years of living in Stepanakert, now that dream has been squashed by the ongoing conflict. “I can’t move back to Syria,” Hovig tells us. “I feel betrayed by the country I grew up in, my second home.”

And for a lot of refugees, this is a shared sentiment. But not only is it emotionally hard to imagine going back.

The conflict has intensified since the Turkish operation on Syria’s Northern border in October 2019. It isn’t safe enough to return. Aleppo was recaptured by the regime and its allies in December 2016, but the government has done little to rebuild the infrastructure and the local economy.

Hovig has been back a few times over the past few years, to collect some items from their apartment, and to buy tree-seedlings for their fruit farm. The state of Syria saddens him. “The road from Damascus to Aleppo used to be an easy four-hour drive, now it can take up to 12 hours — the asphalt is rubble, there are checkpoints, and sometimes a bomb goes off,” Hovig tells me.

Tokmajyan explains to us how Aleppo was not only a major regional market-hub, it was also the industrial powerhouse of Syria. “Aleppo as a city was larger in terms of economy and population than, for example, Armenia. In 2011, Aleppo’s contribution to the GDP was estimated at $15 billion, according to the Aleppo Chamber of Commerce. About $5 billion more than the entire Armenia’s GDP in the same year. This major economic capacity has now declined significantly.” Rebuilding Aleppo’s economic ability requires state intervention in terms of financing, rebuilding infrastructure, water, and electricity, as they are only partially functioning currently. At the same time, sanctions have made the banking system almost paralyzed –– rebuilding your home with no access to trade and finances clearly hamper the return process.

Seven years after they fled the country, the two families made a living and a home in Nagorno-Karabakh. The fruit tree farm they helped set up was finally making some profits, offering the Armenian market fruits previously unavailable, including olives, pistachios, kiwi, and a flat peach. They were the largest producer of that type of peach in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh.

When the land and its trees needed less time and effort from everyone, Hovig and Isabel decided to start their very own cafe, offering the local community not only a different kind of food but also a different environment.

“We realized that Stepanakert is very beautiful and safe at night, but nothing was open late,” says Hovig. Now they serve their customers till the dark of night, seven days a week. “People come back, and every evening the old traditions of a communal culture are coming back. I am happy that my family and I could have an impact like this.”

Although war loomed, for the Dangourians, the war-torn and disputed region had given them a place to call home again. Now, with war raging, they are not considering leaving it behind. When the conflict became intense, they sent their three children to Isabel’s parents, who had settled in Yerevan after fleeing the Syrian war. Isabel and Hovig have stayed in Stepanakert offering locals and war journalists a place to come together over a hot Syrian meal.

Video: George Surguladze

Photography: Elene Shengelia

Additional reporting/production: Anna Kamay

Interactive production team: Lola García-Ajofrín, Marcin Suder, Piotr Kliks

Web development: Piotr Kliks