Junkyard of the West

INTRODUCTION – THE RED STICKERS

Red stickers. Seen from Libya to Cameroon, on the windows of cabs’, private vehicles, and sometimes on crashed cars at police stations. They come, just like these particular cars, from Germany. Many more are from the European Union, Japan, and the USA. The red stickers indicate that marked vehicles were considered high-emitting in the past and were not allowed to enter more than 70 German cities.

For years, however, they could enter the global south. „High-emitting” is a word that does not hamper sales in places like West Africa. There are more terms like that. „Crashed” quickly turns into „straight from Europe” and „salvaged” into „brand new”.

In autumn 2020, a report by the Dutch Ministry of Environment and the other one by the United Nations Environment Program raised the issue. Since January 2021, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) countries have undertaken steps to introduce restrictions.

Today it is clear that it will not be simple. For far too long exporting cars was far too profitable. Africa is getting motorized, and the West is getting rid of inconvenient automobiles. Non-financial costs are easy to ignore.

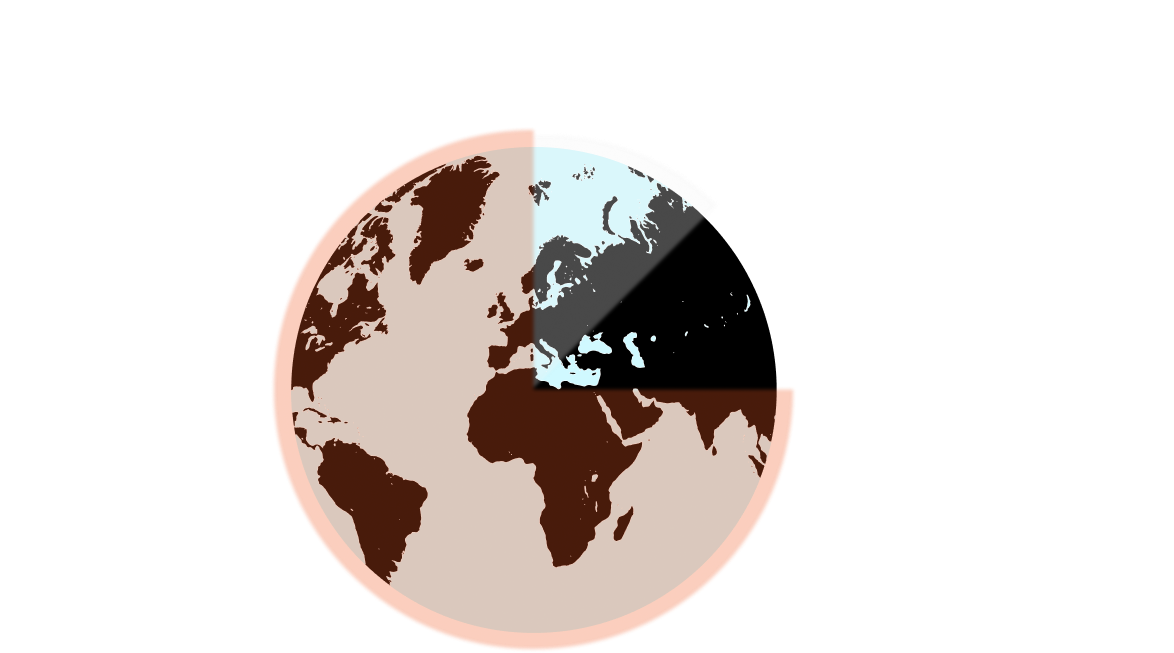

The largest exporter of poor-quality cars is the European Union, and their largest recipient is West Africa.

See the road of the second-hand vehicles.

I. THE ROAD. FROM EUROPEAN NOMADS TO CONTAINER SHIPS

DRIVING THROUGH THE DESERT

The first automobile in Africa appeared on the court of the Ethiopian Emperor, Menelik II, in 1907. A British gentleman named Bentley sent it over the sea and then used it to cross the Danakil Desert, in a way predicting the character of a trade that started some decades later.

The actual wave of cars „to trade” set off through the desert with European travelers in the 1980s. The liberalization of law plus the fact that West African countries like Nigeria found themselves in difficult conditions due to the global recession made foreign car manufacturers close their local factories and assembly lines. It created a vacuum.

„[Then] I met many Germans, French and Dutch who crossed the desert by cars bought in Europe,” says Gerbert. „They took old Mercedes, and Peugeot – especially Peugeot 504 and Mercedes W123 were popular – they traveled across Europe, then transported cars across the Mediterranean, crossed the Sahara and sold them in the south, for example in Mali or Niger.”

Gerbert van der Aa is a historian and journalist from the Netherlands. He has written four books about the Sahara region, including the last one, „In Search of the Tuareg: The Veiled People of the Sahara”. His adventure began in college when he hitchhiked the first time across the desert and discovered that many Europeans use the second-hand cars that they later sell. The following year he bought a Peugeot 505 in Amsterdam and … lost a lot of money. But he gained adventure. A year later, he tried again.

„Cars came off the desert every day back then. Finding a buyer was not a problem. Already at the border, people were asking how much you would sell the car for. If you were lucky enough to buy a nice car cheaply, you could earn something, and you could have holidays for free. (…) I was freelance – the magazines did not want to cover the expenses, so I was working and didn’t have to spend my own money,” says Gerbert.

30 years later, Gerbert has more than 20 transactions under his belt and a similar number of expeditions. It’s by the sold cars that he counts them. He covered every possible route: through Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria. Today he does not buy and sell cars anymore, but the trade continues, although the pandemic slowed it down. „Friends from Mali and Niger still ask me if I would bring them a Land Cruiser”.

Dominika sold a car in Gambia, in early 2020. She described her journey on the dodoknitter.pl blog. The thirty-year-old Mercedes, which they had driven to the Gambia with a friend, was the first car she had. Her father helped her to find it. She chose the model by browsing the most popular cabs in the Gambia, which is a standard method, not only among novice traders.

„Dad went there and asked the salesman whether the car is good enough that the guy would let his own daughter drive it to Africa. The man didn’t want to believe it was a serious question but said yes, he would.”

And he was right. 11 weeks later and several thousand kilometres further, a man from the Gambia bought the car for 10 000 zlotys (roughly 2500 USD). Dominika had paid 2 500 zlotys (around 600 USD) for it and then spent similar amounton repairs. Before leaving, they contacted a local NGO and took a mobile cinema screen with them.

Dominika does not remember where the idea for this particular form of travelling came from – it seemed pretty natural to her. The decisive factor was the need for adventure and the possibility of covering part of the travel costs. „If I have the opportunity, I’ll try again,” she adds.

In travelers’ groups, both on Facebook and other forums, such as Tripadvisor or Lonely Planet, many people are willing to share similar experiences. At times people were fundraising and seeking sponsors.

Voices from those asking for responsibility in bringing old cars to West Africa rarely break through. Especially since it is common for those who already traveled with second-hand cars to receive messages like „When will you bring a new car?” on WhatsApp from people they barely remember meeting.

„Now, few traders from Europe drive through the desert. Some Africans still do that, especially those who live in Europe. (…) For example, the cavalcades go south before Grand Magal, an important Islamic festival in Senegal,” says Gerbert, and several other interlocutors confirm that.

DANCING ON THE DECKS

In the Google search engine – the combination of phrases „used cars” and „Africa” in any popular European language takes the user to offers to buy cars, advertising portals and dedicated Facebook groups. The phrase „in any condition” appears often.

Oloyede is a trader from West Africa, whom I encountered in one of the Facebook groups. When I mention that I would like to sell a car he lists a long list of models. Some of them are surprising, like the Peugeot 206. He is not interested in my Peugeot 307.

What Oloyede buys won’t go across the desert. These cars will go via the sea route, in this case to the Cotonou port in Benin. From there – as the man claims – most will probably go to Nigeria, which is, next to Ghana, the largest recipient in the continent. According to some studies, the network of people involved in that kind of trade reaches not only Europe and Africa but even Lebanon and Pakistan.

„When I was selling cars in Niger, most of them went to Nigeria anyway. (…) Merchants are also happy to send them there via Benin or Togo to avoid paying huge bribes in Nigerian ports,” says Gerbert.

The maritime trade has seen massive growth in popularity in recent decades. Between 1980 and 1990, the volume of dry cargo hardly changed, and the number of containers transferred by land doubled. The growth that followed was unprecedented. By the mid-2000s, more than 90% of world trade traveled through the seas and oceans.

Before the pandemic outbreak, online operators offered individual customers to transport a car from Great Britain to West African countries at the cost of even 600 euros. Emmanuel Dogbevi, an award-winning investigative journalist from Ghana and the creator of Ghana Business News, estimates that importing a car from the US does not cost more than 1000–1200 dollars.: „The repairable car will cost approx. 1000–4000 dollars. A high-class vehicle can cost even 7000 dollars. Another 2500 dollars for a customs agent, and then the cost of car repair. It makes a total of 8000–10 000 dollars. Such a car is considered new. A brand new car would cost at least five times as much.”

Data reported to Outriders by the German Federal Statistical Office provides evidence that although the overall number of cars exported from Germany in 2020 was lower than a year and two years earlier, it increased for almost every West African country and those close to them (such as Cameroon). We are talking about hundreds of thousands (or even millions) of cars, and we are counting only those reflected in the official statistics.

II. THE SECOND (AND THIRD) LIFE OF A CAR

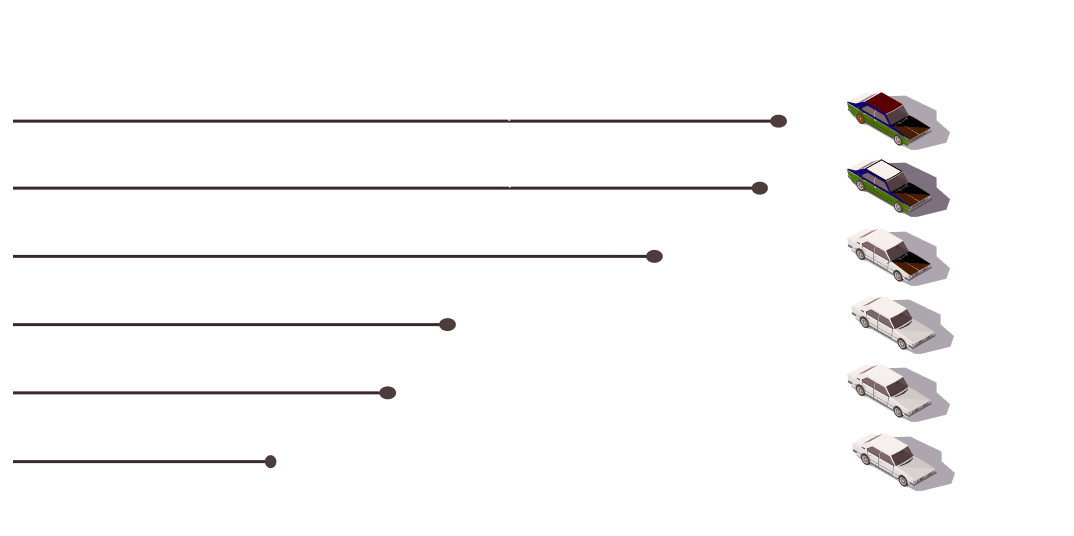

A car that comes off the assembly line in one of the large factories in the European Union is for the first few years usually used by its owner in France, Germany, the Netherlands or another country in Western Europe.

Then there are two options. The first one means: export papers, trip to the port and then to Africa, sometimes also to Central Asia. It is the route for one million cars travelling from the EU to West Africa each year. The second option is exporting from the “rich” EU to the poorer countries such as Poland, Romania and Lithuania.

„We are rather the end-user of cars,” says Adam Małyszko, the Polish Automobile Recycling Forum Association president. Yet, a car that will finish its life east of the Oder still has a chance to go to West Africa. as Małyszko continues: „What can be shipped from us is spare parts.”

THE SECOND LIFE. EXPORT.

„We have a lot of rubbish here. You wouldn’t believe how these cars are smoking.” Kira is the moderator of the West Africa Travelers group and is proactive against sending what she calls „scrap” to the South. She has been living in West Africa for 20 years and works in aviation in Côte d’Ivoire. Officially, that country has one of the best regulations in the region.

Gerbert said, that „Africans don’t buy just anything. They are interested in good, strong cars.” Dominika agrees: „Our Mercedes was a very solid car.”

It’s easy-to-repair classic cars, such as Mercedes w123 and w124, that achieve the best prices. Also, the less iconic but popular ones, like the Seat Alhambra from the 90s or the Peugeot 206, are famous for their reliability. However, the German Federal Statistical Office data shows the tip of the iceberg: the average value of a car shipped from Germany in 2018 to major West African countries was around 1000 euros. Over a dozen times less than the overall average.

The Dutch report from 2020 indicates a peculiar curiosity. The average age of officially exported cars from the Netherlands to Nigeria was close to 18 years, and the Nigerian law prohibited the import of any car older than 15 years at that time …

There are many similar inaccuracies. Together with the growth of legislation, Nigeria has developed a whole system of customs agents – companies focused on helping to pass local controls. Agents have fitted into the landscape so much that even completely legal goods will not leave the port without their help.

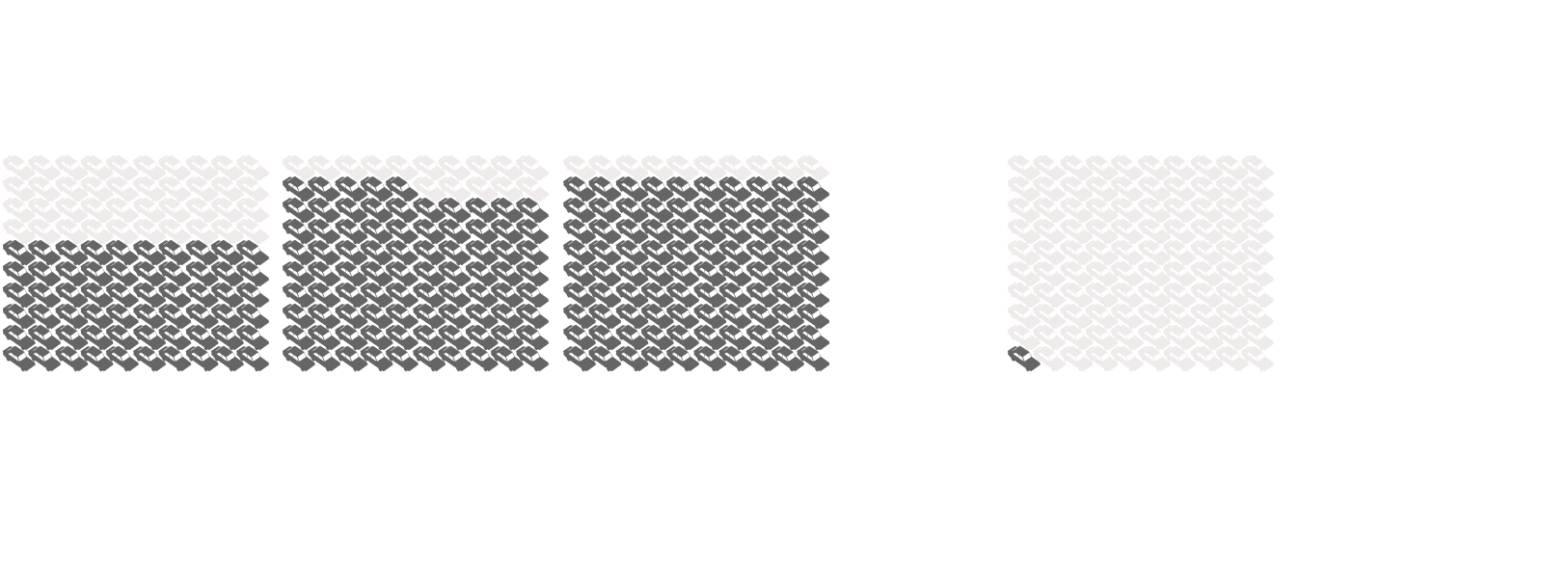

The authors of the aforementioned Dutch report stated that the condition of cars exported from their country to Africa is similar to those that the Netherlands scraps at home. The vast majority did not have up-to-date technical reviews, or they were to expire soon. 80% of cars did not meet the Euro 4 (EC2005) standard, which applies to all cars manufactured after 2006 in Europe. Field studies revealed that 20% of vehicles failed the emission tests, and 14% had either absent or inoperative diesel particulate filters or catalytic converters.

P. [who preferred to remain anonymous] knows that business inside out. Over the years, he has shipped cars, but most of all, thousands of tons of spare car parts from Central Europe to West Africa.

„I can guarantee that 90% of our cars have catalytic converters removed. Most often, they are replaced with a tin, and I doubt that every customs officer knows what the catalytic converter box looks like in every particular car model,” says P.

Reporters working for UNEP state the same opinion in their article. In less official forums, sellers sometimes post ads with two prices per car. One price with the catalytic converter and the other without it. The idea of counter measuring this, however, is somewhat romantic. Even if Europe somehow managed to control nearly a million cars a year strictly, the platinum, palladium and rhodium contained in the catalysts (worth from several dozen to several hundred euros) will be a great temptation in countries where such amount of money is much more than monthly earnings of several dozen per cent of the population.

„I’ve seen Mercedes T1s that looked like they were taken out of the sea after 30 years of lying at the bottom of the sea. But local traders said these cars would drive.” P. also tells about the extremely popular Mercedes Sprinters: „Their story was that they had driven 500 000 km in Germany, 500 000 km in Central and Eastern Europe and when it already seemed that it was total scrap, they went to Africa. And I am convinced that they can drive another million kilometers there, with some repairs.”

Altogether it makes 2 million km, maybe even more. The differences in the wealth of the ECOWAS countries are large. According to the Human Development Index (HDI) and GDP per capita, the economic gap between Ghana and Niger is similar to the gap between Greece and Iraq. That could indicate that many cars may seep through the cross-border trade between the more affluent and more impoverished countries in the region, and quality is likely to decline along the way.

THE THIRD LIFE. SPARE PARTS

One million cars sent to West Africa each year need spare parts. They come mainly from Central Europe. „At one point, we shipped a full 23-ton container of parts, mainly engines, a day,” recalls P.

A large market is Poland, the biggest importer of cars within the EU. it has its ecological impact as well: last fifteen years came with over 85% rise in CO2 emissions there. Meanwhile, for the total of the EU they remained unchanged over this period. Since its admission to the EU almost 14,5 mln cars came to Poland. So, the existence of a large grey area for vehicle recycling there is rather unsurprising.

„It is the last user that is obliged to scrap the vehicle in an environmentally safe way, that is, to hand it over to a vehicle scrapping facility,” explains Jakub Faryś, president of the Polish Automotive Industry Association. „Unfortunately, this is not always the case. It is even said that there is a group of people who have nothing but they are the formal owners of many vehicles that, in practice, are already dismantled. The fact is that there are several million cars in the Central Register of Vehicles that probably do not exist, the so-called dead souls.

Adam Małyszko gives similar information: „Around 1.4 million cars were dismantled in the grey market last year alone (in Poland). That was the number of vehicles without insurance that was added to the statistics over that time.”

No one will guess how much of them hit the local market, how many left, and how many arrived in West Africa. The data is missing. Between 2002 and 2017, the load of spare parts imported into the country increased several times in Senegal. But the total value of spare parts has hardly changed.

There is a photo gallery on one of the largest exporter’s websites: hundreds of car engines are lying on the ground. I make a dozen or so phone calls, but the owners of these places don’t want to talk. Usually, they refuse politely, but sometimes they do it more creatively: „Come on, man, I don’t even know who is taking it from me. I’m just packing it, and they are taking it somewhere. Nobody knows nothing!”

In addition to engines, all large components, such as drive axles, are also exported. A large group of these parts could be classified as waste that is subject to remelting. So why do the European Union officials let them leave the EU?

„You need consultants, a legal office that continuously responds to inquiries from the officials. And that’s a real hassle. It is the vehicle scrapping facility that decides whether an engine is reusable or should it be wasted. There is no clear-cut regulation that would determine this, so it is really up to the scrapping facility to make the decision. In my experience, it is challenging to prove that an engine is a waste,” – says P. Adam Małyszko, president of the Polish Association of Automobile Recycling Forum states: „It is indeed not fully defined when a vehicle is a waste and when it is not. There are guidelines, but that’s not the law”.

An economic calculation is decisive. Remelted parts are many times less valuable than those intended for reuse.

P. claims that: „(…) reusing car parts is the best and most environmentally friendly way of waste management.” However, he admits that he knows many examples of dishonest approaches to business when basically anything was sent … because buyers were ready to buy anything. Finally: not all engines end up in cars. Some are used for other purposes. From boats to water pumps to air conditioners in Chinese buses, as it happens in Ghana. In such cases, of course, they work without catalytic converters or other emission-reducing systems.

„In Ghana, every spare part that arrives from a car disassembled in Europe (or on-site) is defined as new, even car tires that are already several years old. A spare part that is actually brand new is virtually impossible to buy,” says Emmanuel Dogbevi.

The question is, is the making of a new engine certainly less emissive than using the old one for the next few years? And what will be the total emissivity per kilometer in the case of parts produced today, which are still believed to be even several times less durable than the old ones?

„It is our culture – the culture of throwing things away. In Africa, they are doing the real recycling that we’re talking about here. (…) We don’t like when it’s Africans that recycle, but there, on the spot, it has value. Maybe we don’t know how to appreciate the older things? (…) It is a welfare disease that we call something older than ten years trash,” – comments Gerbert van der Aa.

But that’s a lot more complicated than judging whether it is good to recycle something or not. Two issues are also important: what is being recycled, under what conditions and how, and whether regions such as West Africa should actually bear the environmental and health costs associated with it.

III. THE HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL COSTS

THE AIR

„You can almost touch the air pollution in Abidjan. I slept in a room with two of my friends’ children. I couldn’t fall asleep; they were breathing so loudly,” says one of the interviewees.

The topic of poor air quality in African cities, including West Africa, appears in every conversation, both with Africans and tourists and migrants from other continents. And the situation does not make it easier because the region has significantly fewer stations, which regularly monitor air quality than Europe, for example. Depending on the system, there are 2–12 of them for almost 400 million people. The European Union has nearly 5,000 air quality monitoring stations.

UNICEF estimates that the number of people who die prematurely from air pollution (so-called external air pollution, mainly caused by pollution related to industry and transport. It does not include indoor pollution) in Africa has increased from 178 000 in 1990 to 258 000 in 2017. This figure may not sound particularly alarming for a continent of more than 1.2 billion inhabitants. It is also not comparable to the Asian countries, but there are still very few cars in West Africa compared to the rest of the world. And that’s why there will be more and more of them.

Guy Mbayo is a specialist working for the World Health Organization. He worked on the WHO report on Accra, the capital of Ghana, published in 2021. One of the proposed scenarios indicates that changes in transport could save 5 500 human lives in the next several decades and another 35 000 due to the health benefits of increased physical activity like walking or cycling.

RECYCLING

Cars and their parts sometimes make journeys that the great explorers from the past would not be ashamed of. The Polish Chief Inspectorate for Environmental Protection comments:

„In 2019, under the Chief Inspector of Environmental Protection permits, 1,972.5 tons of waste from the processed lead-acid batteries were brought to Poland from Africa. The waste was processed in a special installation used to process lead-acid batteries [used in cars], as a raw material for lead recovery.”

Did some of these batteries come from cars that had been previously sent there from Poland? That’s possible. But that’s not the point. A similar action made in Europe pays off. There is adequate infrastructure for safe recycling and recovery of valuable elements, e.g. from batteries. In West African countries, however, it’s just not possible.

Several years ago, Emmanuel Dogbevi’s coverage of electro-waste sparked a worldwide discussion. Now, he comments for Outriders: „Ghana, in my opinion, doesn’t possess the capabilities to cope with such waste. It does not mean that it cannot develop it, but we are currently unable to deal with ordinary urban rubbish. For example, we can’t recycle plastic.”.

Half of the world’s battery recycling is done informally, often involving children. The situation is changing slowly if any.

„Electro-waste is also a good example,” says Emmanuel. „Ghana relies entirely on German funding to build a proper recycling facility. And it is delayed for political reasons. (…) In the parking of every police station in Ghana there are damaged cars, some stay there for many years, and nobody does anything with it. Is it laziness or something else, or is it just the lack of adequate infrastructure? I don’t know.”

A 2015 report by the WHO Regional Office for Africa cites an estimate that Africa loses around 134 billion dollars annually only because of the impaired intellectual development of children and adolescents associated with their excessive exposure to lead. No wonder, since the UNICEF report from 2020 shows that in West and Central Africa alone, between 85 and 197 million people under the age of 19 have lead levels in their blood which are believed to be elevated and need to be monitored. The latter, the highest estimate would mean that two-thirds of the population under 19 are affected by this problem. In Western Europe, that number ranges from 1.4 to 4.5 million people.

The business around cars and their parts bear probably only a fraction of responsibility for these numbers, but there is a link. The aforementioned WHO report contains a compilation of studies on the pollutants’ sources. Several dozen of them indicate lead as the direct cause of proven poisoning in Senegal, Ghana, and Nigeria, related to the automotive industry, especially informal recycling of batteries (including children working with it), and working in auto shops or scrap yards.

DEATH IN A ROAD ACCIDENT

The final piece in a costly health puzzle is car accidents. While West Africa has very few cars per population, it reigns supreme in accident rates.

„They are definitely dangerous”, P. describes the condition of many cars imported to West Africa. „For example, doors are made on the spot from the sheet of metal because even those coming from Europe were completely corroded.”

„Owning and using a car in Ghana is a public health risk,” says Emmanuel Dogbevi. „(…) Most of the cars that are used as tro tro [a form of local private transport, replacing buses and taxis – editors note] were never meant to be used for transporting passengers in Europe – these are cargo cars made into buses”.

Of course, there must be many more factors again taken under consideration, and the dominant ones are the quality of roads and the lack of regulations or just not obeying the law. In other countries, however, the number of traffic accidents victims is related to the condition of the vehicles and their age.

IV. SOLUTIONS. „THAT’S THE MILLION-DOLLARS QUESTION”

„Wherever we use cars, there is the emission of fumes, but the comfort of life also increases. And so is access to services, removing communication barriers, etc. I do not think that it is important where Africans get their cars from. It is not of greater importance for the environment. The fact is that poorer regions import cars from relatively richer regions, and that’s the norm,” says K. from Poland, who works as a dealer selling used cars.

„If there had been an easy solution to such problems, well, they would have been easily resolved,” adds Gerbert, laughing.

The problem is that the equation is quite simple in assumptions but challenging to solve. West Africa needs transportation; however, its population is too poor to afford new cars. Public transport does not exist, and private transport is dangerous and unreliable. The circulation of cars, both during and after their usage, threatens millions of people in many different ways. In turn, the states are too weak and lack the capacity, and often the political will, to combat these problems effectively.

„You often see a car that, at first glance, shouldn’t be able to pass a technical review,” says J.P., sales manager from the Senegalese capital. It is a country regarded as one of the best in the region in terms of managing the problem – it has a low maximum age of imported cars and a relatively young fleet of vehicles. „In some neighbourhoods of Dakar, the police will stop such cars and keep out of traffic, but in others – or outside the city – there will always be a way to get around it.”

„It’s the million-dollar question,” says Emmanuel Dogbevi as we talk about the potential solutions.

TOO OLD FOR THE IMPORT BUT THE CHEAPEST TO BUY

From January 2021, ECOWAS countries decided to gradually introduce limits on the maximum age of imported cars and fuel quality. Age restrictions, however, raise some doubts.

When the rules on the age of cars were changed in Côte d’Ivoire in 2018, the number of imported cars from Germany dropped dramatically from year to year. But some cars probably only fell outside the statistics.

„It’s easy to recognize a car that has just been imported,” says Kira. „New registration plates are different. And you can see many of them have nothing to do with the age limit that we officially have here.”

„When we were driving through Senegal, we had to get a special passport stamp,” recalls Dominika. „It indicated that we drove in by car, and when we left the country, they checked that stamp. (…) But we arranged it with a fixer, so, anyway, if we wanted to sell the car in Senegal, he would probably be able to arrange it as well.

The age limit for cars in Senegal was introduced in two phases and with a small hiccup when it was found that the change came as too much of a shock. For a while, the maximum age of imported cars had to be raised from five to eight. Overall, however, it is considered a positive example. Cars – especially in the cities – stand out from the rest of the region.

Ghana is still facing all the difficulties and consequences of introducing such a regulation.

„Since 2002, Ghana has implemented age-based restrictions on vehicle import. The allowable age is currently pegged at 10 years beyond which attracts progressive penalties through tax instruments,” comments Guy Mbayo from the WHO. In 2020, Ghana planned to completely ban the import of damaged cars and cars older than ten years. „The implementation of this policy faced some challenges which led to its withdrawal by Government to allow for further consultations.”

The views differ here. There are questions about the infrastructure necessary to repair new cars, their prices and many other problems caused by such a complicated system.

„A friend of mine living in Mali owns a car so modern that no one in the whole country can repair it,” says Gerbert.” I have seen cases of replacing broken engines in new cars with the old engines because they were easier to repair,” he adds.

„In Senegal, we imported knowledge along with new cars. Initially, our mechanics learned in European auto shops and then they came back to repair cars here.Infrastructure came with cars”, says J.P.

Moreover, African wealthy classes like to drive beautiful, expensive cars. In several conversations, both in Senegal, Ghana and Nigeria, there is a reflection on how luxurious – concerning the shape of these countries’ economies – the vehicles moving around the capitals are. Symbols of wealth, but without much real wealth.

Regardless of what restrictions are introduced, people will always look for other ways. As Emmanuel Dogbevi says, „It’s a need-driven situation. If you are in need, you will try a solution that will give you a respite.”

PUBLIC TRANSPORT AND THE FACTORIES

Transportation is a need. Hundreds of millions of people have to move around, and governments cannot help them. Anyway, the question is whether they really try and want to.

„Public transport [in Ghana] is chaotic and extremely frustrating for passengers,” says Emmanuel Dogbevi. „In the 1960s and 1970s, we had a very effective system, called Omnibus Services Authority, but it fell apart due to negligence and sheer corruption. Since then, several attempts have been made to introduce new solutions and each time with no success.”

Minutes later, Emmanuel adds: „Ghana has a fantastic, well-designed transportation system plan for the Accra region; millions of dollars have been spent on it. But the intentions were never implemented.”

„Our economy is service-based, and economies like that rarely create enough jobs. The irony is that there are rich people in Ghana, but there is a void in what to invest in. Private transport is one of those few things that allow you to make a profit – you buy a car and hire the drivers.”

It is an inefficient, dangerous, and unsafe transport. The latter feature mainly determines whether people decide to quit using their vehicles. And so, history comes full circle.

In West Africa, car production is on the rise. Nissan and Volkswagen already have assembly lines in Ghana, as mentioned by Guy Mbayo and Emmanuel Dogbevi. The African brand Innoson operates in Nigeria and sells new cars for less than 10 000 dollars. It is an exciting vision, referring to the 1980s when Peugeot produced tens of thousands of cars a year in Kaduna state. Factories, however, were abandoned during the recession and the worsening economic situation. The IndustriALL Global Union report shows that Sub-Saharan Africa can produce 10 million new cars by 2030, many of them in Ghana and Nigeria.

Today, while locally produced cars are a spark of hope and offer good quality at a competitive price, the path to change still seems long. Even a cheap new car is still too expensive for most West Africans, and there are lots of stumbles and formal obstacles on the way. In Ghana, Volkswagen sells cars with manual transmissions, although automatic ones are preferred. Meanwhile, in Nigeria, Ahmed Wadada Aliyu of Peugeot Automotive Nigeria recently argued on local television that the current rules are not helping local manufacturers to compete effectively with foreign factories and, in some cases, they are even taxed more heavily than the importers.

A QUICK JUMP

In some reports, the quick jump hypothesis is gaining popularity. According to it, West Africa could take advantage of the lack of cars, jumping immediately to the most modern solutions.

WHO’s Guy Mbayo describes it in the context of Ghana: „the Ministry of Transport is working towards adopting an emission-based planning tool for clean fuels including the introduction of policies to influence and advocate for the use of electric vehicles.”

A few days later, I spoke about it to Emmanuel Dogbevi. And he almost laughed.

„Ghana is barely able to provide electricity to meet the basic needs. For the last few months, we have been operating according to the planned power cut-off scheme. Sometimes several hours a day. And even then, the electricity does not always come back on time. (…) Out of every 10 kilowatts produced, two are usually used as a backup … but of the remaining eight, only five go to the recipients. It is a huge structural problem that the government cannot solve.”

Almost every solution faces new problems. Many hours of talks lead to the picture that often contradicts the content of the reports’ recommendations and does not inspire optimism. Will the EU restrictions bring anything if the import from the USA, Japan or Korea is still enormous? Even rich countries do not solve such wide-ranging problems quickly… And none of the ECOWAS countries is rich.

Meanwhile, millions of people not only want but also have to move around. Effectively, relatively quickly, and cheaply. Safety and care for the environment are the privileges of the rich, although their lack most often affects the poor.

However, these problems should not be used as an explanation, and solutions must be sought, even if they seem unreachable for the time being. A situation where selling old, high-emission, and often unsafe cars from Europe (or spare parts) brings 400% gain in West Africa is certainly not normal. It leads to an absurd dilemma: developing countries are too poor to buy cars cheaply.

It remains an open question who should seek the answer. Perhaps everyone. Emmanuel Dogbevi, whose knowledge includes the situation in the most developed and wealthiest countries and cities in the world, refers to the data in a text:

„It seems to me that this issue is akin to the issue of electro-waste. Europe is failing to take responsibility for its pollution and is finding a cheaper and easier way to get rid of it. Suppose the European countries send cars to West Africa for 1 000 euros, knowing that they are dangerous to the environment and would not be allowed to enter many of their cities. In that case, it is a deliberate attempt to get rid of this pollution at the expense of the health and well-being of Africans. (…) This shows low levels of moral accountability. It is up to European countries with a conscience to think through and ask themselves sincerely: is it acceptable to do?”.

Story: Tadeusz Michrowski

Infographics: Juan Carlos Ramírez González

Design: Tadeusz Michrowski & Piotr Kliks

Source of data:

- Growth in the number of cars – based on Transport Energy Data Book, Edition 39, p. 77, p. 85 and the estimates from the UNEP report, p. 3, p.12.

- Transport and passenger vehicles emissions data – Our World in Data based on IEA and ICCT data.

- Percentage of new cars among the cars registered in African countries. ITA data for Ghana and Nigeria.General data for the continent based on the UNEP report, p. 5.

- The number of cars per 1000 people is based on data from WHO. Data for Canada based on datasets from Statistics Canada. Data for the European countries based on Eurostat. Historical data for the USA based on Transport Energy Data Book, Edition 30, p. 79.

- Export of cars to African countries in 2015–2018 based on the UNEP report, p. 20–21.

- The average worth of exports from Germany in 2017-2020based on data provided to Outriders by the Federal Statistical Office of Germany.

- Second-hand cars exported from the Netherlands to Africa – data from the report by the Human Environment and Transport Inspectorate of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management of the Netherlands, p. 37, p. 55.

- The average age of the passenger cars in Europe is based on data from Autoalan Tiedotuskeskus.

- Passenger cars in Poland based on the report by the Polish Automotive Industry Association, p. 25, p. 26and the estimates given by experts during the interviews.

- The impact of the missing catalyst converter is based on data from the International Platinum Group Metals Association.

- Lead levels in the blood of children based on the UNICEF and Pure Earth report, p. 22–23, p. 29.

- Death in roads accidents per 100 000 vehicles based on the report by the WHO African Office.

- The average lifespan of a car is based on the research found in the European Transport Research Review 13/2021.

- Financial losses of African countries do to the high exposure to lead based on the report by the WHO, str. 3.